Hyphen's own Luke Patterson -- that's Mr. Hyphen ('08), to you -- gets graffiti artist Estria talking.

Here's Estria on hard work: "I'm a big advocate for second and third place, folks, cuz they're gonna try real hard to become the first place."

On art: "It's true revolution where it's coming from the heart. As opposed to coming from a place of anger at the way things are, you're coming from a place of love where you want things to be better for people. I think artists, we have a role in that, we can be the voice for our people."

On social activism and graffiti: "So it's not like 'show up and paint your name.' We're trying to shift the social consciousness in graffiti culture across the next 10 to 20 years and making people, instead of 'Me Me Me, my name my name my name,' it's about 'what am I speaking on?'"

Introduce yourself to us, brutha! Why the hell are we talking to you?

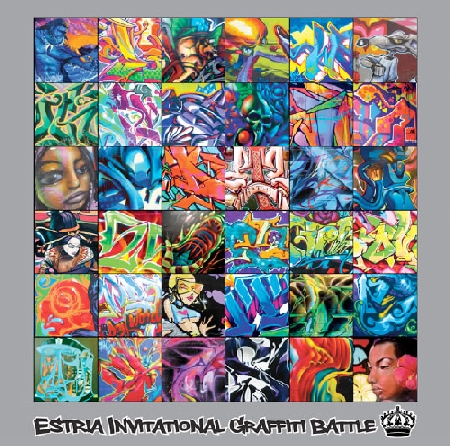

My name is Estria, I've been writing graffiti for over 25 years, and currently I'm heading up the Estria Invitational Graffiti Battle, which is the first national graffiti battle in the United States.

So you said you’ve been a graf writer for over 25 years. Can you give us some background into how you got started and your history within graffiti?

I started in Hawaii, that’s where I'm from. I came up here [to the San Francisco Bay Area] for college, and kept doing the art here. Up here it was on a whole 'nother level than Hawaii, so at the end of college I was like I can't go back, this is my thing. So I just kept doing it, I never tired of it for some reason.

I can’t see how you would tire of it when you have such skills.

You know what, in the beginning I didn’t have those skills. My buddy, still my best friend, he had that natural talent and he could just draw without even trying. That aggravated me cuz I couldn’t do that, so I worked hella hard everyday to get as good as him. So I’m a big advocate for second and third place, folks, cuz they’re gonna try real hard to become the first place.

Who are some of your influences, within graffiti or art in general? Where’d you develop your styles from?

Initially I painted with a couple guys in Hawaii, and I was just clueless. I didn’t know that I sucked until I came up to California. The first time I painted was with a guy named Crayone, he was one of the kings of San Francisco at that time. I painted with him and his crew, they had graffiti at a level that I just couldn’t comprehend. They were painting big crazy things, they had several styles under their belt. They had character styles, production skills, they were really doing it big, and I was like wow I wanna get as good as these guys. So Crayone was a huge influence on me in terms of expanding my horizons of what’s possible for me to paint. Then through the years other people have inspired me in lettering. There was this guy Raven from Pittsburgh, Concord area. He was a style master, he no longer paints but he inspired me for years to get real funky and explorative with my letters. He’s the one who made lettering fun for me.

You have a real nationwide influence there. In L.A., there’re lots of writers who only get influence from other South Central writers, or valley writers, or the Hollywood scene; don’t really venture out of their box. But you seem to have much broader horizons, which speaks to how your invitational event has become an entire nationwide event. Could you explain a little more about the battle to us?

There’s the Mighty 4 break battle that goes around the country, they’re in 30-something cities a year. Then you have the competitions in Europe both in breaking and in graffiti, and they’re huge. And we have nothing like that in the graf element in the States. We did this for a couple years in Oakland, and it was a hit. Each time the vibe was real cool, people really wanted to come check it out or participate, the response was surprising to us. So last year we were like “let’s take it nationwide, let’s do that!” So we lined up a few cities and made it happen. Each city was a trip, people would tell us “thank you for bringing this, we needed a shot in the arm into our local scene, because maybe everyone’s thought of doing this, but nobody’s done it. And you’re coming from outside in, bringing this to us.” So for example in New York -- and these are the old school cats -- they’re telling me that we’ve never had a graffiti-centric event before. You might have the Rock Steady Crew Reunion, but that’s B-Boy centric. Or they had a block party for something else, the thing that echoed it, but they’re not on the same scale that we’re doing, the thoroughness of researching folks and reaching out to the leaders in the field, trying to make sure it’s a cool event, people not having beef with each other. So it was really cool. […]

But yeah we just felt that what we were doing in the Bay, we were mixing our progressive community activist/organizing skills with our art. Yo, the Bay straight up has it on lock when it comes to community organizing. So we were like, “Yo we’re gonna share these skills with other people, set up these festivals, rock it, and get the art world out of their institutions and into the hood, into the streets, into the parks and share it with folks. We’re gonna get folks more savvy on the arts, get folks participating. There’s a whole lot of different good things that can come out of these projects.

I really like that I’ve seen a lot of your work that has value in and for the community, from your Malcolm X murals to Media Justice poster designs for Third World Majority and other orgs. Your work speaks to the movement and community involvement a lot. What role you feel your work or art in general plays within such movements?

I think creative people, whether musicians or visual artists, dancers, what have you, they tend to be more open minded because they tend not to fit into boxes very well. So they’re used to thinking creatively, and they’re also used to questioning how the government or society is set up where they live. So if you look historically when revolutions happen, it’s not uncommon for the artists to be killed first off, ya know. Look at the shit Fela [Kuti] was saying, you know they wanted to get him! Or Bob Marley, that’s radical stuff, still radical to this day. And it’s true revolution where it’s coming from the heart. As opposed to coming from a place of anger at the way things are, you’re coming from a place of love where you want things to be better for people. I think artists, we have a role in that, we can be the voice for our people. […] And not to say that ALL the work has to be revolutionary, but I think culture is revolutionary, and we’re trying to level that out instead of having cultures get wiped off the face of the earth.

For me, graffiti in L.A. was one of the few places I saw all different ethnicities hanging out together, and was one of the few places I didn’t feel somewhat an outsider or outcast. What role do you see yourself playing as an Asian Am graf artists, how has your experience been with that?

When I’ve traveled to L.A., it’s exactly how you said, and the Bay Area, San Francisco specifically, you had groups of Asians doing graffiti, you had black folks, Latinos, Whites, India Indians, you’ve got everybody, it’s great. And on the West Coast, some of the most influential graf writers have been Asian, or at least part Asian. So in the same way that the Skratch Pickles made a huge impact on DJ culture, just a little homie crew of Filipino cats, that’s how graff has been too. Just we haven’t gotten so famous off that, but the impact has been equally as big.

Any other info on the upcoming battle? Anything you wanna speak on?

There are going to be other graf battles coming down the road from other people in the country, but I think what sets us off is that we’ve kept to our roots and had the activist part, the consciousness part in what we’re painting. Every battle we use a word that has the possibility for positive messaging or empowerment. So the words have been things like "life" or "alive" and in those things we’re trying to talk about how many young men of color are getting killed in the streets. This stuff is really critical. Or AIDS, you can talk about those things with the artwork. We did a piece where it was "earth" in Chicago, and all the artists were talking about how we’re destroying the Earth. And in Hawaii the message was “Makai,” which means towards the ocean. So it’s not like “show up and paint your name.” We’re trying to shift the social consciousness in graffiti culture across the next 10 to 20 years and making people, instead of “Me Me Me, my name my name my name,” it’s about “what am I speaking on?”

And we’ve also been really big on trying to encourage women to participate. They tend to not like the battle mentality, and there are very few women in this thing anyway because it’s a grubby, dirty contact sport. Whatever women we can get to join the battles, they’re in. It’s like that seventh generation thinking of the Native Americans, “How will my decision affect seven generations down the road?” Our thinking here is, if we have women painting or judging, and little kids are at the festivals checking it out, say a little girl that likes doing art sees a women artist getting down, then she starts thinking “I can do it too.” They don’t have in their mind that they’re excluded or marginalized. So we’re shifting the gender equity right there, equality right there. It’s like that word sankofa, return to your roots, they let you know where you’re going forward. And if I return to my roots in my home and in my family, you don’t treat women as second class citizens, you treat them as equals. So why should we do that any different in our graf culture? We shouldn’t.

Comments