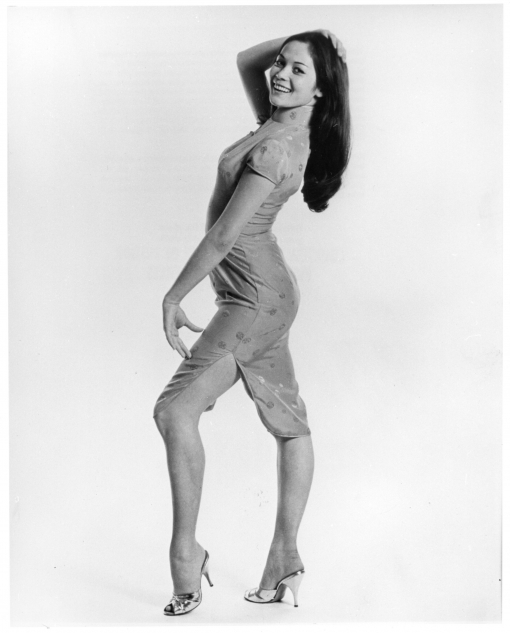

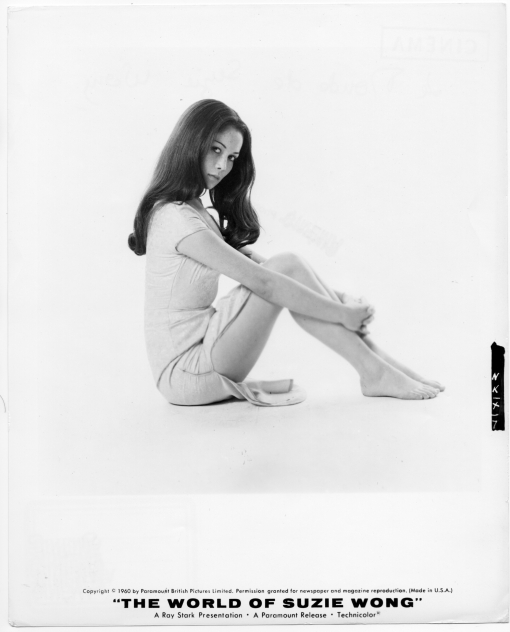

It was an accidental audition, one that 20-year-old Nancy Kwan stumbled upon while peering in on Hong Kong actors vying for the much-coveted Hollywood movie role of Suzie Wong. Wearing a wine-colored cheongsam with her hair coiffed into a sleek bun, Kwan smiled broadly at the camera, answering questions about the pronunciation of her name and taking graceful, profile-revealing turns in patent leather heels. Kwan, who had no prior acting experience, was on the verge of making movie history.

This turn of fate opens To Whom It May Concern: Ka Shen’s Journey, a new documentary from director Brian Jamieson. As a long-time fan of Kwan and executive at Warner Bros.’ home entertainment division, Jamieson began researching Kwan’s life when the studio was considering a re-release of four of her films. The documentary, which is currently touring the film festival circuit in the United States and internationally, details Kwan’s life and the role that defined her career.

The World of Suzie Wong became a hit in 1960 and made Kwan, the daughter of a Chinese architect and an aspiring English actress, a star. The role also made her a trailblazer for Asian actors in an era when Hollywood still used white actors for Asian roles. But in the 50 years since its theatrical release, cultural critics have cast Suzie Wong as a sanitized and exoticized depiction of a prostitute. A “cute, giggling, dancing sex machine with a heart of gold,” novelist Jessica Hagedorn wrote of the character in an essay titled “Asian Women in Film: No Joy, No Luck.”

The movie recounts the relationship between American artist Robert Lomax, played by William Holden, and Kwan’s titular character, a Hong Kong prostitute. At first, Lomax holds the tart and seductive Suzie at arm’s length. However, with sly persistence, Suzie inserts herself into the painter’s life, becoming his muse and eventually his lover. The movie’s romance between a confident American man and a beautiful Asian woman replicated a paradigm that had been long established — and perpetuated — in Hollywood.

Yet, in spite of the movie’s portrayal of prostitution and Asian females, Jamieson argues that Kwan turned out a memorable performance, adding dimensionality and charm that counters what critics have viewed as Suzie Wong’s stereotypical subservience and exotification.

“She comes across as this vivacious young girl who just delivered the lines so naturally,” Jamieson says. “As a result, [Kwan] gives [Suzie Wong] something of herself, some of her own personality. I really think it was all of that magic and mix that ultimately carried the day for that character.”

However, many audiences, especially Asian audiences, didn’t see it that way. “When it was released, I got asked by Chinese and Asians, ‘Well, she’s a prostitute. Do you think all Asian women are prostitutes?’” Kwan says.

Now 71, Kwan takes the criticism in stride: “It was a strong woman’s role. And a wonderful role for an actor. That’s how I looked at it. It was just entertainment.”

The World of Suzie Wong was a rare opportunity in Hollywood for an Asian actor. Previously, very few were offered leading roles; Asian American actors like Anna May Wong and Keye Luke took a backseat to their white counterparts. More marketable white actors, such as Luise Rainer and Jennifer Jones, with the aid of elaborate costumes and “Orientalizing” eye makeup, assumed roles written for Asian characters in such major Hollywood productions as The Good Earth (1937) and Love Is a Many Splendored Thing (1955).

“[Hollywood] didn’t think they could make money by having a Chinese actress in the lead,” Jamieson says. “When Nancy got the role of The World of Suzie Wong, she didn’t realize it at the time, but she was making history. That ultimately opened the doors and changed the status of other Asians to follow.”

Jamieson believes that Suzie Wong was a catalyst, for better or worse. “Suddenly people were conscious of the ‘Orient,’ ” he says.

As a result, Jamieson says, “you had all of these Westerners wanting to go to Hong Kong to find their Suzie Wong. But maybe not in a bad way, maybe in a good way.” Jamieson believes this pursuit of Suzie Wong by Westerners fostered more liberal ideas about interracial relationships. Ultimately, the documentary repositions Kwan’s role as glamorous and pioneering rather than a softened or sensualized image of Asia for white audiences.

It was Kwan’s ease and humor in front of the camera, as well as the box office success of The World of Suzie Wong, that led to her other defining role as the brassy Linda Low in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Flower Drum Song (1961). While she would eventually appear in over 50 films and television shows, including playing an acrobatic circus performer in The Main Attraction (1962) and as Bruce Lee’s mentor in Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1993), her subsequent career would never match her early successes.

Both Jamieson and Kwan see the trajectory of her career as the result of the profit-driven nature of the film industry, as well as fluctuating attitudes toward Asians in the United States. Despite the financial success of Suzie Wong, the belief that Asian actors could not bring in numbers at the box office lingered in Hollywood; therefore, few roles were assigned or generated for Asian stars. The public’s dissatisfaction with American involvement in the Vietnam War led to a significant decrease in the demand for Asian-themed movies.

Additionally, Jamieson says that Hollywood has always been reluctant to cast Asians or Asian Americans in characters “outside the culture,” a premise he disagrees with. In the Clint Eastwood and Meryl Streep film The Bridges of Madison County, for example, “Why couldn’t it have been Clint Eastwood and Nancy Kwan?” he says, jokingly.

While his documentary wrestles with the uneven path of Kwan’s acting career, fleshing out the untold story of Kwan’s personal life became a chief concern for Jamieson. In the final act, the film turns its focus toward Kwan’s only child, Bernhard Pock, who died of AIDS at age 33. Jamieson draws a telling comparison between this and the death of Suzie Wong’s infant baby in a disastrous mudslide in The World of Suzie Wong.

“There was something prophetic about it in the sense that Nancy would lose her only child under the most tragic of circumstances,” Jamieson says.

In fact, that is what Jamieson believes The World of Suzie Wong was really about, not merely a story of a prostitute. “It was a beautiful love story about a woman trying to overcome her own circumstances, raising a child,” he says. “Nancy also had this enduring love story with her only son.”

In the 50 years since The World of Suzie Wong premiered, there have not been many film roles played by an Asian or Asian American actor that have produced such fervent dialogue and scholarship as that of Suzie Wong. Today, Kwan believes that there are few such defining roles written for or by Asian Americans.

While she encourages young Asians and Asian Americans to pursue acting and work behind the camera, Kwan does not see herself as an Asian or Asian American actor. Instead, Kwan’s identity is rooted in a firm adherence to her craft, as well as a loyalty to the characters she portrayed.

“I identify as an actor,” she says. “That’s what I am.”

Learn more about the documentary or purchase a DVD at

Comments